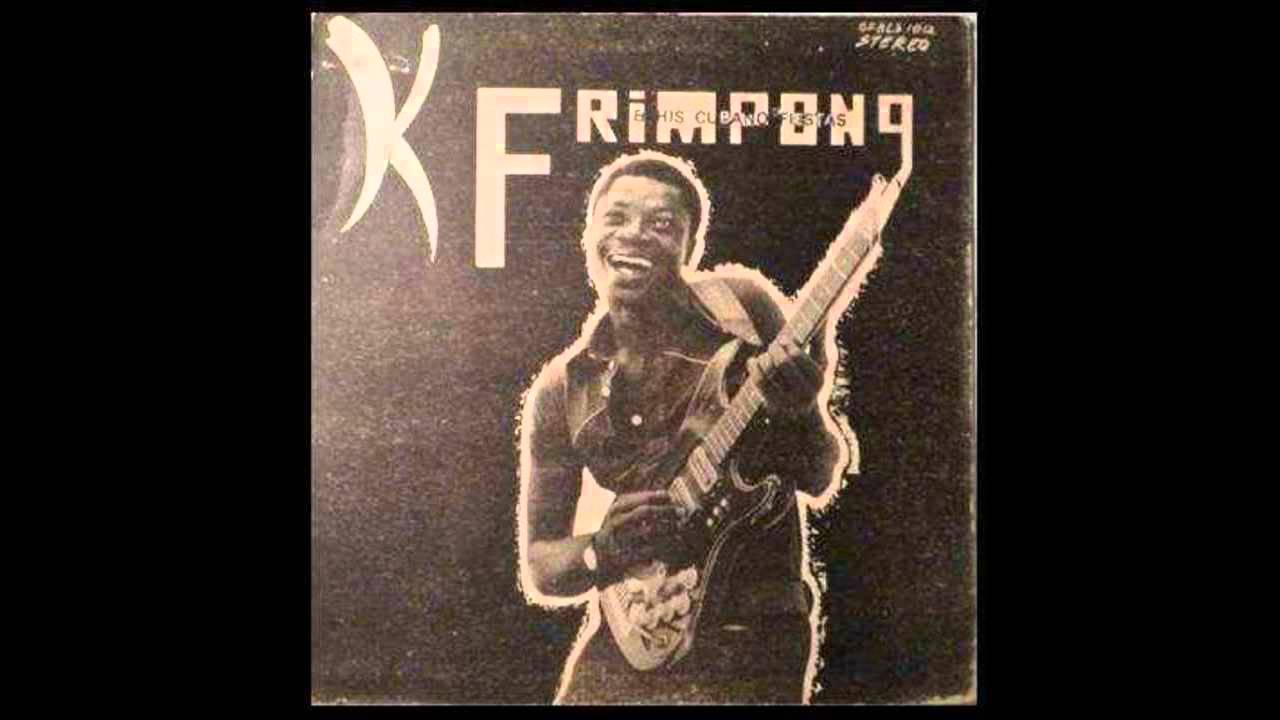

Song: Hwehwe Mu Na Yi Yo MpenaArtist: K. Frimpong & His Cubano FiestasAlbum: K. Frimpong & His Cubano FiestasReleased: Ofo Bros - OFBLS 1012 (LP) Ghana 1977.Writers: Alhaji Kwabena Frimpong

[audio mp3="https://blackloveproject.files.wordpress.com/2015/03/09-hwehwe-mu-na-yi-wo-mpena.mp3"][/audio]

Independence Day. March 6, 1957.

At long last, the battle has ended! And thus, Ghana, your beloved country is free forever! Osagyefo Dr. Kwame Nkrumah (March 6, 1957)

And with these words, Ghana became the first African nation to gain its independence from Europe. I make the distinction of using the word gain, to stress that Ghanaians were not given autonomy over our land, we fought to control what is rightfully ours. We all know that independence is taken and not given. Revolutions do not just happen over tea and biscuits. Or fufu and soup for that matter. It is important that we remember the revolutionaries who fought British colonialism before independence, specifically Yaa Asantewaa, one of the most important women in Ghanaian history.Kwame Nkrumah, the first president of a liberated Ghana spoke widely about the philosophy of Pan-Africanism, which asserts the need for a global black community, one that shares an understanding of cultural, historical and socio-political aspects of black people. If one looks at the movement of African Independence, beginning with Ghana in 1957, there is a clear parallel between this and the American Civil Rights Movement. There was an international parallel of black struggle for autonomy. Nkrumah recognized this, and spoke adamantly about the African man understanding and showcasing his brilliance, without the crutch of European hands and pockets. This idea that black men recognizing their capabilities would generate a successful people, resonated through the Continent and Diaspora.

June 19, 1950. Keta, Volta Region, Ghana, West Africa

My father and maternal grandfather are from Keta, in the Volta Region of Ghana, West Africa. My father is a tall and proud man, as are most African men. It took me becoming an adult and him moving to Ghana, for me to fully grasp how Ghanaian my father is. By his very breath and existence he is Ghanaian. The normalcies of my childhood, were in part cultural lessons and preservation. The traditions and nuances I hold dear are things I will tell my children to remember. For example, receiving things and eating with your right hand. This was something taught as my father would feed me small, rounded handfuls of fufu he'd dipped into steaming bowl of okra stew. Learning to remember and honor my ancestors, by Western measures nothing more than tribal voodoo, was given to me through our frequent libations. Speaking in Ewe, he would would call out the names of our ancestors, asking them to guide and protect us. There would be a handle of gin and roots, a glass of water and black eyed peas or farina as offerings. It is customary for each person to taste the gin and water, to share a toast with your family. In thirds, he would then offer the gin, water and food. I remember always feeling very moved when he would speak the names of those who'd gone before us, but through libations and reverence were with us still. Or even just watching my father tend to his garden, of tall stalks of okra and corn. Boiling ground nuts and making me sweet potato custard. As a child, you don't understand the importance of traditions passed down, they seem very common place. However, as I am growing to know myself these seemingly common traditions, become increasingly important in my identity. My African heritage is something that I intensely honor. It is the thing that made me.

Gold All on My Watch and Other Cultural Leanings

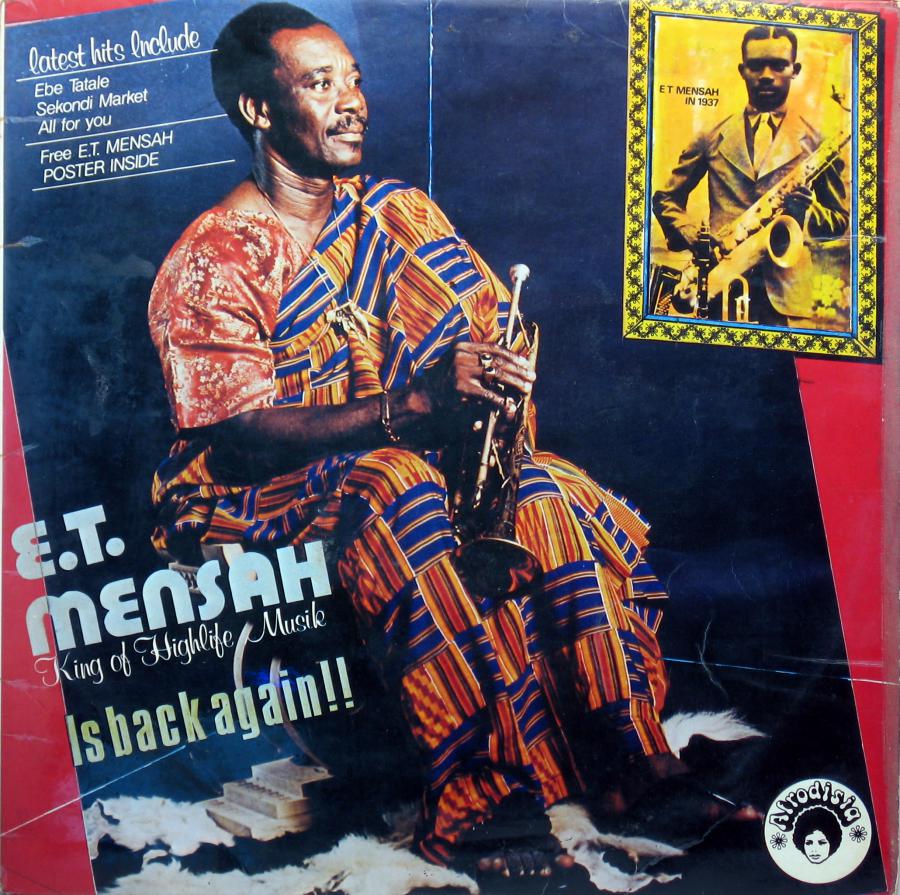

I grew up in a house filled with music. Most Saturday evenings, our house was filled with music, the smell of a clean house, and something stewing on the stove. This tradition my parents gave to me the love for the very thing Africans created; music. The music of their generation consists mainly of traditional African rhythms influenced by the funk and jazz of America. Highlife is a genre that is strictly Ghanaian. Striking horns borrowed from jazz, plucky guitars, a steady base and drum beat and a maintenance of Ghanaian vocal structure, these are the bones of highlife music. These are the songs that remind me of my childhood and my people. The songs are long and meant to be danced to, meant to be enjoyed. This need for rhythm and movement, is an inherently African expression of life and one that can be seen throughout the Diaspora.

As far as I can remember, we have always been a gold wearing family. You will not find silver 'round these parts. Before independence, Ghana was called the Gold Cost, aptly named for the thing Europeans were stealing the most of. The Ashanti believe that gold is a reflection of the sun, the source of life. You will find chiefs draped in gold, from head to toe. This natural inclination towards gold has traveled with the Diaspora, showing in the gold in our watches, necklaces and teeth. We've always been a gold people. The kente cloth that is so frequently used throughout the Diaspora as a symbol for Africa, is strictly Ghanaian. These, amongst so many other traditions, are the things that Ghana has given to the world.