Chay Chay Poley: A Quick Lesson on Liberian English

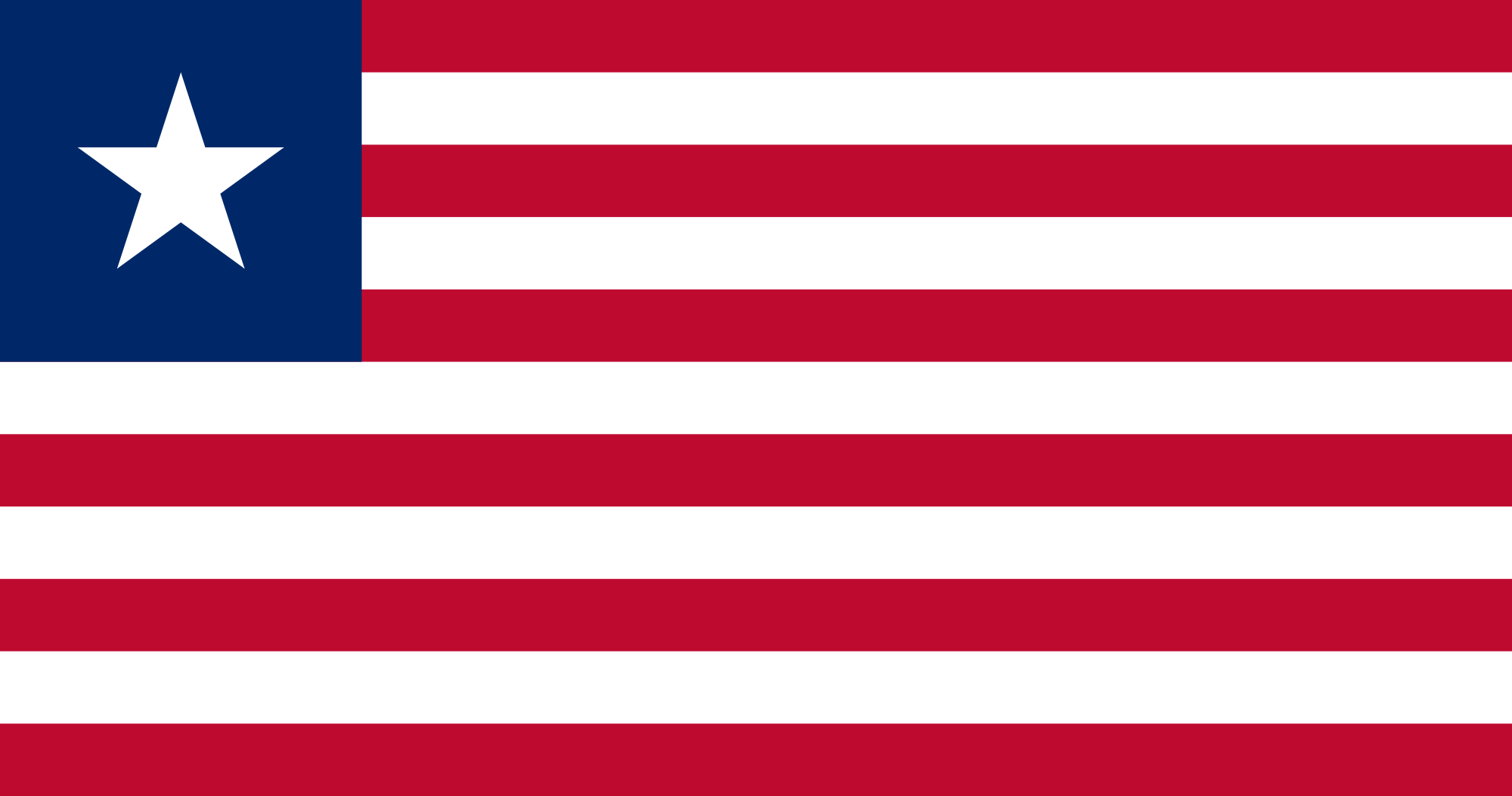

[audio m4a="https://blackloveproject.files.wordpress.com/2016/07/01-chay-chay-poley.m4a"][/audio]Song: Chay Chay PoleyArtist: Tokay TomahThe linguistics of the Diaspora is fascinating to me. No matter where we landed or remained, our tongues have been influenced by colonization. West Africa is known for its various forms of Pidgin or broken English, the West Indies for their patois and the United States for AAVE. When we look at these variances of Black people learning European languages, the syntax and patterns are often similar across the Diaspora. Noun verb agreement, order of words, inflections and speed, deletion of consonants; all of these things point to the linguistic and comprehensive nature of indigenous African languages and the overall evolution of the syntax Black people. There are many parallels in the spoken languages of the Diaspora. For Liberian English, there is a close relationship to AAVE, given the influence of freed American slaves.As Liberia celebrates its 169th birthday, I think it fitting to pay attention not just to our history of war; but to our culture and traditions. As language and words define a culture, I want to discuss the unique vocabulary and expressions of Liberian Engligh, known as "colloqua". The Liberian accent is like no other; spoken quickly and melodically. There are tonal inflections that indicate whether an exclamation stands alone or is in support of an independent clause. For example, "o" an exclamation that when used by itself, shortly and with an upward inflection means disbelief. When expressed longly, there is downward inflection and denotes sorrow. However, the same "o", placed at the end of a sentence is merely for support of the main idea, like, "I hungry, o.", this time, the "o" has little upward inflection and is there to support how hungry one is. Even the pronunciation of the letter "r", pronounced "ara", I thought R. Kelly was Ara Kelly for a very long time.Liberians are by nature a happy people, always ready for a good time. I think the accent is very telling of our that. We speak in song and riddle. Liberia, with a population of indigenous Liberians, freed slaves from the Americas, and a Caribbean population mixed to create one of the best accents across the Continent.Fellow Liberians, feel free to add to the list in the comments section! Happy 26th o!Quick Guide to Liberian Englishla/ley: theda: thatyor: you all, y'allo: exclamation. used by itself, often in disbelief. or at the end of a sentence. either short or long in sound, at variance. example: i hungry, o.enh: suffix used as a question. example: you hungry, enh? or, you must be hungry, huh? also means and.yah: suffix. used at the end of a sentence for emphasis or affirmation.mehn: man. also used as emphasis or support.jue: girl, womanold man/old ma: term of respect for elderseh yah: exclamation said in lamentation or remembrance.eh mehn: exclamation said in pity, sadness, or disappointmentjust now/jeh now: quickly. right now. at this moment.hobojo: a loose woman. prostituteyor how do o?: how are you?business: matters or affairs. example: that man business nah easy. or things concerning men aren't pleasant.fini: has finished. has occurred. completely. example: i fini eating long time. or i ate a while ago.fini give: gavego-come: to go and return in a short period of timetoo bad: very much. example: I want him, too, too bad.to the: answer to question of someone/thing's location. example: where is Mary? She to the house.da lie: you're lying. that's a lie.nyama nyama: small thing. trivial things.don't add my frustration up: don't make me angry dry: skinny. thin.different-different: various typesplum: mangobutter pear: avocadoground nut/ground pea: peanutgoo goo: good good. tasty. pleasant. example: da goo goo woman. example: that's a good/pleasant woman.country: referring to indigenous people, culture, traditionswaste: spilled. example: da whole thing waste or everything spilled out.what place?: where? example: da what place you at?why you looking so?: what's wrong with you?(but) wait now: hold up. similar to AAVE hol'upI coming go: I'm about to leavedress (small): move over. move to the side.make shame: to embarrasskwi: Americo-Liberian, Congo, bougieplenty: a lot of. example: she made plenty rice. Similar to AAVE use.fine boy/girl: term of endearment. attractive man or womanyou boy/you girl: term of endearment. similar to AAVE use of boy, girl in conversationso-so: nothing but. example: so-so women were there. or there was nothing but women there.my people: referring to a group of people. or to one's family. can also be used alone in lamentation. example: o, my people o."pronounced "my pee-po"your people: used when inquiring of another's family.move from here: stop complaining to me. can be used in disagreance.for true: for realhelluva: big, large.vex: angrysmall-small: a little; in amount or distancesweet: good. delicious. enjoyable. example: "dis rice eh swee' o."take time: be careful. A child's song sings, I was passing by/my aunty called me in/and she said to me/Jewel take time in life./You got far way to gopalava: trouble or argumentcarry: to bring somewhere. "come carry me to the store."doka flea: used clothingyou will see me: to show one self. said in anger.wetin . . .?: what thing? suffix to da, "da wetin?" or what's the problem?chay chay poley: a gossiper.da force?: have i forced you? (asked rhetorically)

[audio m4a="https://blackloveproject.files.wordpress.com/2016/07/01-chay-chay-poley.m4a"][/audio]Song: Chay Chay PoleyArtist: Tokay TomahThe linguistics of the Diaspora is fascinating to me. No matter where we landed or remained, our tongues have been influenced by colonization. West Africa is known for its various forms of Pidgin or broken English, the West Indies for their patois and the United States for AAVE. When we look at these variances of Black people learning European languages, the syntax and patterns are often similar across the Diaspora. Noun verb agreement, order of words, inflections and speed, deletion of consonants; all of these things point to the linguistic and comprehensive nature of indigenous African languages and the overall evolution of the syntax Black people. There are many parallels in the spoken languages of the Diaspora. For Liberian English, there is a close relationship to AAVE, given the influence of freed American slaves.As Liberia celebrates its 169th birthday, I think it fitting to pay attention not just to our history of war; but to our culture and traditions. As language and words define a culture, I want to discuss the unique vocabulary and expressions of Liberian Engligh, known as "colloqua". The Liberian accent is like no other; spoken quickly and melodically. There are tonal inflections that indicate whether an exclamation stands alone or is in support of an independent clause. For example, "o" an exclamation that when used by itself, shortly and with an upward inflection means disbelief. When expressed longly, there is downward inflection and denotes sorrow. However, the same "o", placed at the end of a sentence is merely for support of the main idea, like, "I hungry, o.", this time, the "o" has little upward inflection and is there to support how hungry one is. Even the pronunciation of the letter "r", pronounced "ara", I thought R. Kelly was Ara Kelly for a very long time.Liberians are by nature a happy people, always ready for a good time. I think the accent is very telling of our that. We speak in song and riddle. Liberia, with a population of indigenous Liberians, freed slaves from the Americas, and a Caribbean population mixed to create one of the best accents across the Continent.Fellow Liberians, feel free to add to the list in the comments section! Happy 26th o!Quick Guide to Liberian Englishla/ley: theda: thatyor: you all, y'allo: exclamation. used by itself, often in disbelief. or at the end of a sentence. either short or long in sound, at variance. example: i hungry, o.enh: suffix used as a question. example: you hungry, enh? or, you must be hungry, huh? also means and.yah: suffix. used at the end of a sentence for emphasis or affirmation.mehn: man. also used as emphasis or support.jue: girl, womanold man/old ma: term of respect for elderseh yah: exclamation said in lamentation or remembrance.eh mehn: exclamation said in pity, sadness, or disappointmentjust now/jeh now: quickly. right now. at this moment.hobojo: a loose woman. prostituteyor how do o?: how are you?business: matters or affairs. example: that man business nah easy. or things concerning men aren't pleasant.fini: has finished. has occurred. completely. example: i fini eating long time. or i ate a while ago.fini give: gavego-come: to go and return in a short period of timetoo bad: very much. example: I want him, too, too bad.to the: answer to question of someone/thing's location. example: where is Mary? She to the house.da lie: you're lying. that's a lie.nyama nyama: small thing. trivial things.don't add my frustration up: don't make me angry dry: skinny. thin.different-different: various typesplum: mangobutter pear: avocadoground nut/ground pea: peanutgoo goo: good good. tasty. pleasant. example: da goo goo woman. example: that's a good/pleasant woman.country: referring to indigenous people, culture, traditionswaste: spilled. example: da whole thing waste or everything spilled out.what place?: where? example: da what place you at?why you looking so?: what's wrong with you?(but) wait now: hold up. similar to AAVE hol'upI coming go: I'm about to leavedress (small): move over. move to the side.make shame: to embarrasskwi: Americo-Liberian, Congo, bougieplenty: a lot of. example: she made plenty rice. Similar to AAVE use.fine boy/girl: term of endearment. attractive man or womanyou boy/you girl: term of endearment. similar to AAVE use of boy, girl in conversationso-so: nothing but. example: so-so women were there. or there was nothing but women there.my people: referring to a group of people. or to one's family. can also be used alone in lamentation. example: o, my people o."pronounced "my pee-po"your people: used when inquiring of another's family.move from here: stop complaining to me. can be used in disagreance.for true: for realhelluva: big, large.vex: angrysmall-small: a little; in amount or distancesweet: good. delicious. enjoyable. example: "dis rice eh swee' o."take time: be careful. A child's song sings, I was passing by/my aunty called me in/and she said to me/Jewel take time in life./You got far way to gopalava: trouble or argumentcarry: to bring somewhere. "come carry me to the store."doka flea: used clothingyou will see me: to show one self. said in anger.wetin . . .?: what thing? suffix to da, "da wetin?" or what's the problem?chay chay poley: a gossiper.da force?: have i forced you? (asked rhetorically)