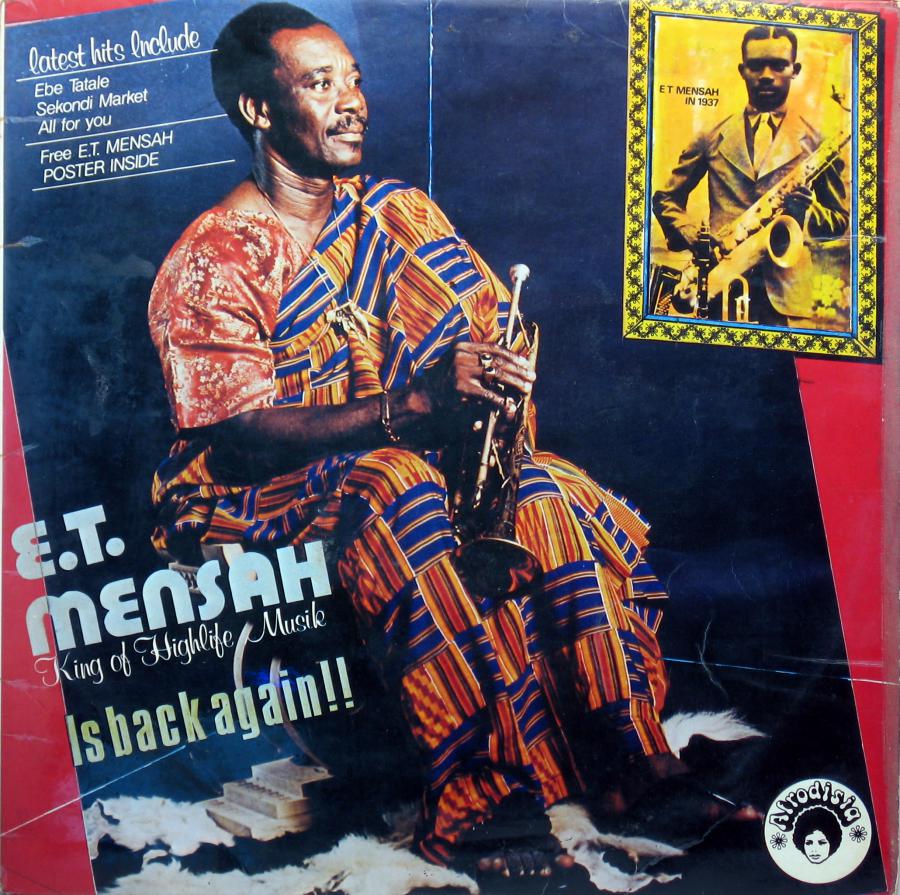

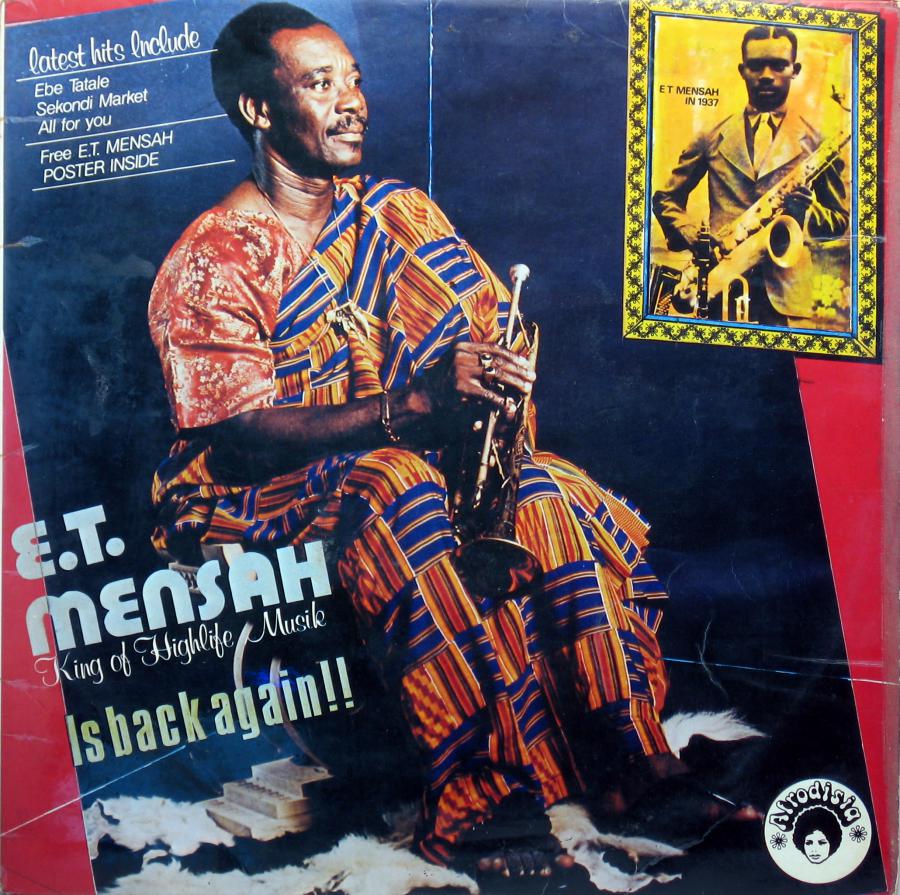

[audio mp3="https://blackloveproject.files.wordpress.com/2016/03/05-abele.mp3"][/audio] My father and maternal grandfather are from Keta, Ghana, West Africa. There was never a time that I did not have a deep sense of pride in being Ghanaian. One of the greatest cultural traditions my father gave me is Ghanaian music, particularly highlife. At any given time in our household, highlife played and was as common as the air we breathed. It accompanies some of the strongest memories I have of my father, so in turn I hold it very dearly. It reminds me of the warmth of Ghana, distinctly African and proud, the fufu and okra stew my father fed me with his right hand, the feeling of embarrassment for being too American when being taught to dance traditional Ewe dances, wishing I spoke the language but feeling like home when I heard it; this is everything highlife evokes within me. For me, there is a a deeply cultural and historical connection to the music of my father's land.Ghana became an independent nation on March 6, 1957, under the leadership of Osagyefo Dr. Kwame Nkrumah. It is with Ghana's independence that we see a deep sense of black pride spread across the Continent in a quest for liberation. As history shows, Africans and the Diaspora continuously create even while under oppressive circumstances. Ghana was no different. The long arms of colonization reached into the musical sector of its former colony. Through European military music, Ghanaian musicians were introduced to brass instruments and European tempo and time-signature. By the late 19th century, the more expensive brass instruments were replaced with traditional African drums and singing and it is here we have the birth of Adaha, the earliest form of highlife. As the new genre moved inward towards places like the Volta Region, it became more African, using local languages and traditional circular African dancing rather than military procession. The Ewe people of Ghana call this borborbor music, the particular form of highlife played in my youth. We also see an exchange of the Diaspora's interpretation of brass music. West Indian soldiers stationed in Ghana brought with them calypso, while Ghanaian musicians like trumpeter E.T. Mensah and percussionist Kofi Ghanaba travelled to America to study the jazz coming out of New Orleans and other cities. There is a distinct parallel and connection in the creation of highlife, calypso and New Orleans brass band music. Adaha was officially coined as highlife in the 1920s, as its increasing popularity found its way into high society events. Reimagined street music had found its way uptown.Music cannot escape politics and politically, highlife gained greater importance during the infancy years of Ghana. President Nkrumah urged musicians to create and artists in turn spoke candidly about their support of Ghanaian independence, as heard in ET Mensah's Ghana Freedom, in which he sings, "Ghana, we now have freedom. Ghana, land of freedom. Toils of the brave and the sweat of their labor. Toils of the brave which have brought results." In the 60s and 70s, highlife's influence travelled across Africa, most notably to Nigerian artist Fela Kuti, who began his musical career as a highlife artist. Artists like Sweet Talks, TO Jazz Band and K. Frimpong and His Cuban Fiestas dominated the scene, experimenting with guitars, Afrobeat and the funk coming from the Diaspora in America. Modern artists like Daddy Lumba use more synth based sounds and artists like Kontihene helped create hiplife, which is highlife tuned into the sounds of American hip hop; all variations founded in the early methods of highlife.Highlife is essentially Ghanaian independence in musical form. The one thing colonialism couldn't steal from Ghanaian people was our ability to create. And as years of colonialism drew to an end, we see the steady erasure of European elements that infiltrated the music. Abele is a song that demonstrates the peak moment of artists shunning European ideals with a greater embrace for all things black African. Artists like E.T. Mensah stand as political figures in Ghanaian history, as he and many others freely created fully in their blackness and against oppression. It is in highlife that we find the soul of Ghanaian music, but also the retelling of our rise to freedom.Happy Independence Day, Ghana. God bless our homeland Ghana. Check out the list of some of my favorite highlife songs:

[audio mp3="https://blackloveproject.files.wordpress.com/2016/03/05-abele.mp3"][/audio] My father and maternal grandfather are from Keta, Ghana, West Africa. There was never a time that I did not have a deep sense of pride in being Ghanaian. One of the greatest cultural traditions my father gave me is Ghanaian music, particularly highlife. At any given time in our household, highlife played and was as common as the air we breathed. It accompanies some of the strongest memories I have of my father, so in turn I hold it very dearly. It reminds me of the warmth of Ghana, distinctly African and proud, the fufu and okra stew my father fed me with his right hand, the feeling of embarrassment for being too American when being taught to dance traditional Ewe dances, wishing I spoke the language but feeling like home when I heard it; this is everything highlife evokes within me. For me, there is a a deeply cultural and historical connection to the music of my father's land.Ghana became an independent nation on March 6, 1957, under the leadership of Osagyefo Dr. Kwame Nkrumah. It is with Ghana's independence that we see a deep sense of black pride spread across the Continent in a quest for liberation. As history shows, Africans and the Diaspora continuously create even while under oppressive circumstances. Ghana was no different. The long arms of colonization reached into the musical sector of its former colony. Through European military music, Ghanaian musicians were introduced to brass instruments and European tempo and time-signature. By the late 19th century, the more expensive brass instruments were replaced with traditional African drums and singing and it is here we have the birth of Adaha, the earliest form of highlife. As the new genre moved inward towards places like the Volta Region, it became more African, using local languages and traditional circular African dancing rather than military procession. The Ewe people of Ghana call this borborbor music, the particular form of highlife played in my youth. We also see an exchange of the Diaspora's interpretation of brass music. West Indian soldiers stationed in Ghana brought with them calypso, while Ghanaian musicians like trumpeter E.T. Mensah and percussionist Kofi Ghanaba travelled to America to study the jazz coming out of New Orleans and other cities. There is a distinct parallel and connection in the creation of highlife, calypso and New Orleans brass band music. Adaha was officially coined as highlife in the 1920s, as its increasing popularity found its way into high society events. Reimagined street music had found its way uptown.Music cannot escape politics and politically, highlife gained greater importance during the infancy years of Ghana. President Nkrumah urged musicians to create and artists in turn spoke candidly about their support of Ghanaian independence, as heard in ET Mensah's Ghana Freedom, in which he sings, "Ghana, we now have freedom. Ghana, land of freedom. Toils of the brave and the sweat of their labor. Toils of the brave which have brought results." In the 60s and 70s, highlife's influence travelled across Africa, most notably to Nigerian artist Fela Kuti, who began his musical career as a highlife artist. Artists like Sweet Talks, TO Jazz Band and K. Frimpong and His Cuban Fiestas dominated the scene, experimenting with guitars, Afrobeat and the funk coming from the Diaspora in America. Modern artists like Daddy Lumba use more synth based sounds and artists like Kontihene helped create hiplife, which is highlife tuned into the sounds of American hip hop; all variations founded in the early methods of highlife.Highlife is essentially Ghanaian independence in musical form. The one thing colonialism couldn't steal from Ghanaian people was our ability to create. And as years of colonialism drew to an end, we see the steady erasure of European elements that infiltrated the music. Abele is a song that demonstrates the peak moment of artists shunning European ideals with a greater embrace for all things black African. Artists like E.T. Mensah stand as political figures in Ghanaian history, as he and many others freely created fully in their blackness and against oppression. It is in highlife that we find the soul of Ghanaian music, but also the retelling of our rise to freedom.Happy Independence Day, Ghana. God bless our homeland Ghana. Check out the list of some of my favorite highlife songs:

- Adjoa, Sweet Talks

- Hwehwe Mu Na Yi Wo Mpena, K. Frimpong & His Cuban Fiestas

- Owuo Adaadaa Me, T.O. Jazz Band

- Nye Asem Hwe, City Boys Band

- Madamfo Pa Beko, Kontihene

Song: AbeleArtist: E.T. Mensah and His Tempo's Dance BandAlbum: Decca Presents: E.T. Mensah and His Tempo's Dance BandReleased: 1963, Decca (West Africa), United KingdomWriter: Mensah, E.T.Mensah, E.T. 1957. “Ghana Freedom” Africa, 50 Years of Music: 50 Years of Independence. West Africa CD1: Track 1 . Discograph LC 14868-3218462.